Ron Sluik & Irina Grabovan

This is my House: The Cruel Paradise

Ron Sluik is an artist born in the Netherlands in 1961. He practiced video- and project-art and other genres, but since he moved to Moldova about three years ago, when he fell in love with the director of the independent gallery AoRTa in Chișinău, Irina Grabovan, Sluik did exclusively photography. He has taught various video and photography workshops in Moldova since 1997, and has guided some Moldovan artists in their work. He has also helped introduce to Moldova a large number of notable foreign artists, such as Ulay and Bertien von Manen among others. In the spring of 2003 Sluik and Grabovan co-authored a book of photographs Sluik made in Moldova, This Is My House: The Cruel Paradise, distributed worldwide by IDEA Books Amsterdam.

Iulian Robu, ArtHoc magazine journalist based in Chișinău, spoke with Sluik and Grabovan about their book.

I.R.: Your book looks, to me and many other people, like old Soviet picture books. Was this intentional or was this the way it came out because the subject was an old Soviet place?

R.S.: The thing is that, first of all, when I came to live in Moldova approximately three years ago, at the beginning I really wanted to work with the material I could find here not only putting myself in another context but also working with the material from here. I knew from the beginning that the book was going to be printed in Moldova and distributed from Moldova, the photos were going to be made in Moldova, printed in Moldova, developed in Moldova. In 1992 I had already made a book which I tried to disguise as if it were made in the 1930s. And it worked. Now I didn't want to make a book which "was made" in the Soviet Union, but I wanted to make a book which would not actually fit in time like in the time of one month or one year; as the photographer I wanted to give the book a kind of timelessness. To make a Soviet book is almost impossible, because the printers and publishing houses in Moldova were so stupid that they threw away everything - they no longer have the old machines; they bought instead cheap second-hand machines in the West. So being a Dutchman I went for the best printer and the best price to print the book. Irina and I kept the design of the book simple, straightforward; we did not try to make a book of the 21st century, so the colors are off, which produced a book that looks to some people as if it were from the Soviet era. For me it's much more interesting to say that the book cannot be put in time, or in a decade. Some of the photos in it look as if they were made in the 1920s, others as if in the 1950s, and still they all were made by the same photographer.

I.R.: Is this because nothing changed in Moldova in the last 15-20 years?

R.S.: It's not about if anything changed in Moldova but in how I perceive it. First of all, the book is autobiographical and the photos included in the book were made in my first year in Moldova. Also, they are my photos, what I see, it's not what the Moldovans see it's just how I see Moldova. The book is not about trying to make a Soviet book. What I try to do in photography is not to make one nice photo but to put photos in a context, and that's the nice thing in the book, because some of the photos are very bad on their own, they are just horrible.

I.G.: What do you mean - the subject?

R.S.: No, as a photo in itself.

I.G.: Knowing you, and knowing myself, and knowing how we did it, I think that it was important that the photos we selected for the book showed visually that what was before was not worse than what happened after. Visually, the last ten years didn't make this territory more beautiful. What is beautiful here is nature, or people, but from the social point of view how architecture represents human activity, how the town organizes human life all this didn't get better. And this is our statement. I didn't think about this before, only now I started to think about it, when you asked the question. When we selected the pictures, we selected for the past, because at least there were those solid buildings, not this cheap, stupid Turkish plastic. For example, in Mon Café on Stefan cel Mare Boulevard they build a cheap plastic terrace on the main street of Chișinău. I am sorry, you can't do that. Of course, this is not Rome or Venice, but the street Stefan cel Mare was planned by good architects who organized it as a unit - this is an organized, whole environment, with a well-planned ensemble. And then somebody puts a plastic extension on a building in the center of the central street!

R.S.: It would make a beautiful new book, on how privatization has an influence on architecture. One of the things you will not find in the West, not even in Romania, is when people living on the ground-floor flats in old apartment buildings make a dacha next to their flat not thinking about their neighbours not having any light any more, and they plant vineyards there and so on. Photographically, this is more than beautiful, but that's not in this book. This book started from my idea to show in pictures how I became a new citizen in a country I didn't know. And the thing was that I identified myself with things I knew about Moldova, and this was the Soviet past and Lenin. So I wanted to visit Lenin monuments in

villages and towns, asking with the help of Irina for directions. And people would say, he is not here any more, or, what a stupid question. Or, they would tell us where the Lenin monument was but it wouldn't be there any more, and I would find a piece of concrete or a little sign saying, this is where Stefan cel Mare [Moldova's legendary medieval king] is going to be

I.G.:

or Eminescu [a classical poet]. There are two iconic figures now.

R.S.: Also what surprised me during that period when we were traveling trying to find Lenin monuments was that so many people had already forgotten, within ten years, where a particular monument was. We met old people, who had lived all their lives in the same town, and when we asked them, where the statue of Lenin was, they would say, it was there, or was it?

I.G.: Often they confused it for the Monument to the Unknown Soldier.

R.S.: We even came to a village and there we saw a group of young children born probably in the early 90s. We asked them, we heard there is a Lenin statue somewhere in this area, and they said, yes, we know, he's still standing there, it's a man with a beard. And we went to the monument and it was a monument to a Soviet hero, who had a beard. So anybody with a beard for a nine-year old or twelve-year old was Lenin.

I.R.: And when you did find a Lenin, why did you shoot him without a head, or only part of it?

R.S.: No, in the book there is a full Lenin too.

I.R.: I mean the photos in which the Lenin is not full in the picture.

R.S.: There is a photo where he doesn't have a head, and there is another photo where I look over his shoulder, in Dubasari.

I.G.: And there is a photo where we can see only his shoes.

R.S.: But I think Lenin could be recognized by his shoes! And there is also this photo where Lenin is without a head, but his name is on the statue; there are hundreds of ways to make a photo, but there are two main ways. One is to give all the information and then the picture doesn't need a title, and you have everything in it; and another way is to leave some space for somebody else to fill in what the photo is about. I like social photography, I like photography in context and it's not only about what I see and what I want to tell, but I find it interesting that somebody else who looks at the photo can make his own story too. So, with the Lenin-without-a-head photo, which is the first in the book, in the West it's directly recognized as a typical Soviet photo the background, the colors an epitome of the Soviet Union. While here, in this part of Europe people will say, it isn't a Soviet photo, because this is the first time somebody makes a photo of Lenin without a head. And there is actually a third way of making a photo: A very nice painter from Moldova saw this photo and he looked behind the statue. He didn't even see Lenin but he saw the building in the background, which is the old council house or culture house, and he saw this bird in the window. And he said, that's my painting, my studio is there. I did not make it intentionally, but this is a photographer's dream.

I.G.: When we printed this photo, it was for that matter very important for you to make this bird clear in the background.

R.S.: And then half a year later, this painter says, that's my studio there. Then there is this photo from Dubasari, where I made a picture of Lenin looking into an alley, while I stood behind him making a picture of what he was seeing. Then later I met a journalist who told me, do you see this house on the right? When I was a student I lived there. So there are different ways of looking at a photo and I think this is what I want to show in a picture. I am a photographer who is not interested in the center of the photo. When I look at a picture, what I want to have in the center is already there and it will be sharp because it's already there, and it's not going to move because it knows I am making a photo of it. It doesn't have to be only a statue, it can also be a person, for example if I were to make a picture of you. At that moment for me as a photographer you are not interesting any more - you are the subject of the photo, but you are no longer interesting. What is going on around you becomes interesting.

I.G.: Not "not interesting." You just have your central subject under your control.

R.S.: One very good photographer who is by far more capable of doing this better than me is Bertien von Manen. She makes snapshots in many countries - in Russia, China. And you always see that there is a subject in the middle, but there is also a little hand coming into the frame to pick a piece of bread, or there is a person moving away from a table, and she gets the picture while the other subjects become the most important element in the photo. Without these surrounding details there is no photo. I think of a photo in my book, Lenin in Cahul, where there are two trees standing spread out. I had this idea that the trees really spread out for me, because they were standing in the way, but they cleared the view for me.

I.G.: Wherever you go, whether the Lenin monument is still there or not, the space is organized around the monument. That is why people react to details in the picture - Lenin is the center, you don't even see him because you have become used to him; he is like the archetype in the Soviet period, when everything was organized in a radial system around the main square with Lenin in the center of it. So, all life was specially organized to support the main core - the Lenin statue. Sometimes you don't even have to ask where the statue of Lenin is - you can determine it by intuition because it is where everything converges in concentric circles.

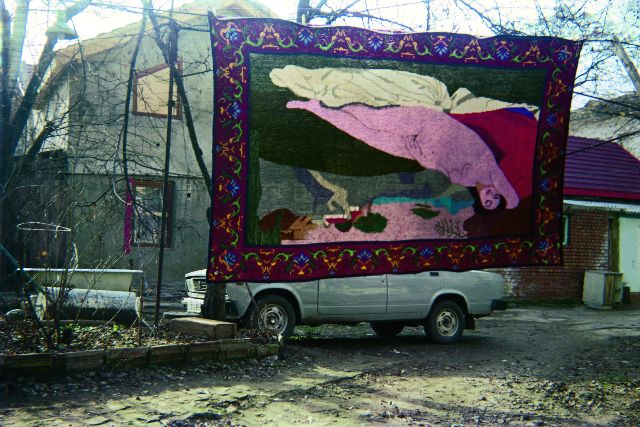

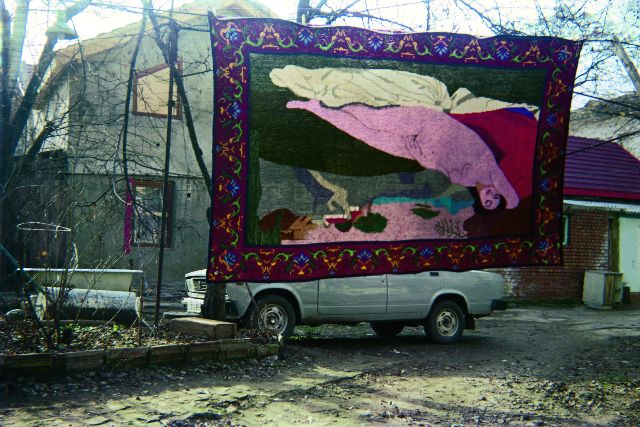

R.S.: So, one of the hidden things in the book is that besides Lenin there is a second subject, which is that Lenin represents the past in the book, or the tool to get to the past of Moldova or of the former Soviet Union. But in the whole book, after the Lenin without a head there is a photo of pioneer Irina, and also there is an upside-down carpet with Venus, and there is a girl with a mobile phone, there is also a young girl passing a fountain - this is the contemporary Moldova, it's there too. The biggest export product of Moldova these days are women, and in the book there are two color pictures of a "shifted" girl in a park, and I "shifted" the photos so much that you don't even see the girl any more, but if you start counting - I never did - there are more girls in the book than Lenins.

I.G.: And in Moldova too there are more girls than Lenins.

R.S.: I tried to put in the book also a link to the present. A lot of people in Moldova asked me, why is the subtitle of your book The Cruel Paradise? This is My House is a clear statement: I moved as a West European to the East and said, this is my new house. This is a long discussion, but it's all about centers: where is the center of being? I decided one day, for many-many reasons, to change my center.

I.R.: What is for you in Moldova "cruel" and what is "paradise"?

R.S.: When people in Moldova saw the book, many asked me, but where is the paradise? Probably in the West people would ask, but where is the cruelty? So there are again two different ways of looking at how to make a photo, how you can perceive a photo, but also how to look at a photo. You can take a photo and write ten thousand words to it; you can write a book about a single photo. That's the beauty of photography. I come from a world where everything is in the center. I was in the center, I was the center of the center and the center was dealing with the center around it. When I came to Moldova with the decision to live here, I thought that I was going to live on the periphery. The book is showing the border where at the beginning I started with a lot of black&white photography, and I focused mainly on Lenin monuments, on the past - the past of the periphery where I was going. Then suddenly there are extremely colorful photos in the book. During the compilation of the book I realized I was not on the periphery, I was actually in the center. The book is a border book - it traveled and came to a border but without crossing it yet. So the title Eto moi dom [This is my house] is a good choice. But this is actually the title of another book, which will say Eto moi dom. The bus shelter on the cover means that the book is still traveling, it's going somewhere; the book is not a statement, it's a search. You can also see this where there is a mixture of B&W and color. The best photo in the book, for me as the photographer, is the one with chimneys and a cigarette box, the third from the beginning. This is by far the best!

I.G.: Why?

R.S.: Because it shows that the world is square. The beauty of a book is that, at least for the photographer who makes it, you can make a book and say, that's it, I don't have to make another one. But in my own book I discovered new things. When I opened it later, I reread it and relooked at the photos. There are some photos which tell me something more now. I wish that a lot of West European artists did the same as me; and luckily I am not the only one, there are more artists moving East. But at this moment there are more people from Moldova moving West than the other way around. After having lived here for almost three years, people in Moldova who know me say, Ron, at the beginning I thought it was beautiful that you moved here, but why are you still here? I needed the book to tell me this story, because sometimes I too don't know. And when I look at this photo with the cigarette box - and most people don't realize it's a cigarette box the photo shows that the world is square, it's not round. And probably this photo is the key to moving on to the next step. This fits with how people perceive, because many people think they live on the periphery and many think they live in the center. Everybody thinks they know the world is round, but it isn't. The world is like a cigarette box.

I.G.: What I think is important in photography, and this is what I understood while working on this project, is that you look at photography in a different way than at painting. You need to change your optics. The quality of reality in photography is quite different from reality in painting. You need to change the level of perception to see reality through the photo camera as your tool. And moving from West to East, with a camera rather than a brush in your hand, having around yourself not Dutch or English but Moldovan or Russian, changes your perception. And this is the best an artist could get: a different angle that you would never have in your usual surroundings. And then you acquire a totally different way of dealing with reality, you get a totally different quality catching it. I think that in this book there is this subtaste of dealing with reality. Living in this "glocal" world, you don't know who you are and where you are, your identity is lost. And when you do this trick, when you move, you come to a point where you can identify the squareness and the roundness of the world.

R.S.: This is why the next book will be called "Moldavisch blauw" in Dutch.

I.R.: Which in English means?

R.S.: Which in English means "Moldovan blue", because it's connected to Delft blue, from the country where I come from.

Interview by Iulian Robu

All photographs are from the book Ron Sluik: This Is My House, the Cruel Paradise. Published by Aorta - Chișinău, 2003.

More information about Ron Sluik and AoRTa: www.art-aorta.narod.ru, e-mail:sluik@gmx.net.